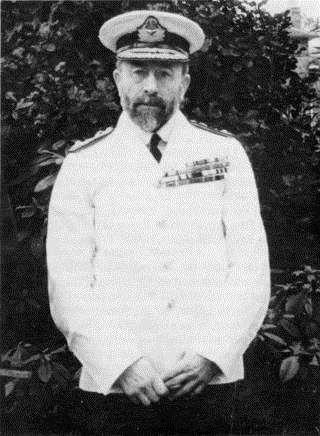

Maximilian

JOHN

Ludwick

WESTON

1872-1950

Pioneer Aviator and Overland

Traveller

ADMIRALTY ESTATES

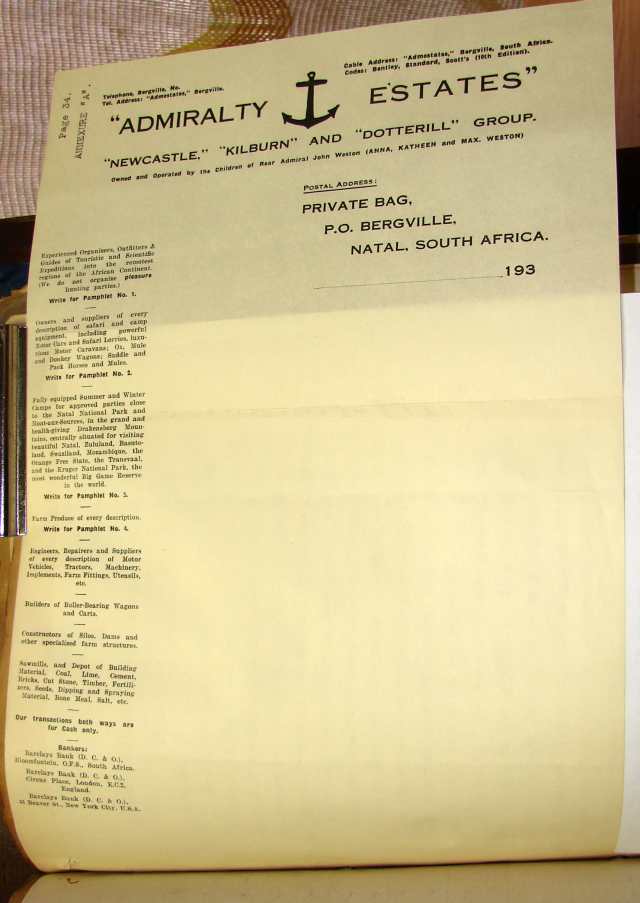

In June 1933 Weston paid £5,500 for three farms (Newcastle 2378, Kilburn 2466 and subdivision A of the District of Bergville in Natal) and named the property Admiralty Estates [1]. The farms covered 10,000 acres but would later be reduced to just over 6,000 [2]. 36 miles of fencing and 500 head of cattle were amongst the many early investments made by the new owner [3].

Admiralty Estates’ headed notepaper read like a manifesto. In the margin it set out Weston’s grand design for his new property. It was to be the hub of an eclectic enterprise

-

organising, outfitting and guiding “Touristic and Scientific Expeditions… into the remotest regions of the African Continent” (“Write for Pamphlet No.1”);

-

supplying “every description of safari and camp equipment” including motor caravans and other vehicles (“…Pamphlet No.2”);

-

offering “Fully equipped Summer and Winter camps” across southern Africa (“…Pamphlet No.3”);

-

selling “Farm produce of every description” (“…Pamphlet No.4”).

If that were not ambitious enough, Admiralty Estates could supply every type of vehicle and every item of farm equipment, could build wagons and carts, could construct silos and dams, and sold a wide range of building materials [4].

According to the letterhead the enterprise was “Owned and Operated by the Children of Rear Admiral John Weston (ANNA, KATHEEN [sic], and MAX. WESTON)” and although only cash transactions would be entertained, the global character of the firm was abundantly clear in the location of the company’s bank accounts – in Barclays’ branches in Bloemfontein, London and New York [5]. Weston told F A de Jager, the son of the man selling the property, that he was buying it “because he feared a currency devaluation and considered investment in fixed property the best course to adopt” [6].

There may have been some truth in that. After all, this was the Great Depression and Weston had a reputation among his friends as “a hard businessman” [7]: “…in business matters he gave no quarter and showed no sentiment” said one of them [8]. However, they did not regard him as a farmer. His friend Professor Jackson “could see he knew nothing of farming” [9], an assertion made more than 15 years after the purchase of the farms!

Almost nothing of this expansive vision was to be realised despite the excellence of the location: today, the neighbouring Drakensbergs are a World Heritage Site and one of the most significant tourist destinations in South Africa. However, the critical factor in Weston’s failure to deliver his grand design was not agricultural ignorance but family breakdown.

There is no doubt that this fracture struck at the project’s core motivation. The involvement of his three children was driven by the traumatic event, mentioned earlier, in Weston’s early life. In a letter to Kathleen in 1941, he confessed that “my separation from my parents in youth… has always weighed upon me as the saddest tragedy of my life”. And, he continued, “it is this fact that had been the primary motive of the… scheme, a scheme that would provide an interesting and healthy living to all while permitting the whole family to remain united” [10]. As stated earlier, there is no solid information as to when the “separation from my parents” occurred though it must have been before his move to Liège in 1888. Just why it happened remains a mystery not least because Weston’s own explanation is opaque: it was “imposed by wrong social & economic organisation [sic]” [11].

In this context the prominence on the notepaper of “Owned and Operated by the Children” [12] is unsurprising and most important. Despite this Weston failed to transfer ownership and, when pressed by his offspring, refused to put their legacy on a transparent and firm basis. Instead he demanded that family relationships should be based on trust, not formal documents. As a result, by 1937-1938 the children (now in their twenties and thirties) had abandoned the scheme and left the family home [13].

The breach between Anna and Max and their father was especially bitter. Weston thought Kathleen was not without fault but gave her “the benefit of the doubt” [14]. He maintained contact and in 1941 wrote to her that “Anna & Max’s attitude was one of downright hostility and of distrust of my integrity… Anna and Max are dead for me”. He also mentions his “refusal to see [them], & anything or anybody connected with them” [15]. Three years later he was still in the same frame of mind: “The peculiar bonds uniting parents & child have their roots in mutual confidence… The moment one side loses confidence in the other their bonds are broken and the disillusionment that ensues renders further association too bitter to be continued. That is what happened in the case of Anna & Max… Both demanded a written agreement as to their future in relation to this estate… This demand was an unexpected thunderbolt and from that moment all the plans I had made to secure the children’s future crumbled down” [16]. His refusal to meet them was still active as late as 1950 [17].

However the departure of the children and his toxic feelings towards two of them did not mean Weston lost interest in the business. Sometime in the late 1930s he advertised for three associates to invest £10,000 each to progress his scheme [18]. There were no replies [19] and the threat of world war, followed by the war itself, must have killed any lingering hope that this plan could be resurrected.

For many years the estate carried vivid reminders of his failed vision. Circa 1950, in a letter to a company interested in purchasing a block of land, Weston wrote “Everything is practically brand new, much of it being still in original cases” [20]. Yet despite this disappointment Weston continued to run the business with support from paid staff, together with intermittent and then full-time assistance from Kathleen and her future husband, Carl Rein [21]. But Weston was not happy. He wrote that, following the break-up of the family, “Mrs. Weston and I found ourselves saddled with a kind of property which would keep us prisoners in uncongenial surroundings” [22].

By late 1944 he considered selling as he felt he was getting too old to continue farming [23]. This prompted Kathleen to make an offer and in mid-1945 an agreement appears to have been made. She would manage the estate, with a quid pro quo that she would make an annual payment to her father and would inherit the property on his death [24].

However when Weston passed away, his will (dated 14 February 1950, only months before he died) made no mention of this [25]. Moreover neither his nor Kathleen’s copy of an alleged agreement in writing could be traced though there was ample circumstantial evidence that an arrangement had been in place for some years [26]. The result was a three year legal battle that pitted Kathleen and her husband Carl against the combined forces of her mother, her sister and her brother [27].

The wanderlust that characterised Weston’s life never evaporated and no doubt played a part in his feeling of imprisonment on the farm. During the 1930s and 1940s, Weston travelled to Europe occasionally and also around South Africa [28]. Sleeping in the motorhome, he would stay in the gardens of friends for several weeks at a time [29]. One friend quoted Weston as saying that “in his caravan he was free to roam the world, and he was at home wherever he went in the world” [30].

In 1946 Weston is recorded as “reconditioning… my motor caravan chassis, for which I am waiting spares from America” [31] but, dedicated though he was to the motorhoming life, he also considered buying a yacht in which to travel the globe [32].

Shortly before his death, Weston told a neighbour he was planning to go to Russia soon [33] though this may have been connected with his health. His travels certainly included medical excursions: he was showing signs of age. By 1948 he was seriously concerned he might go blind [34]. According to his daughter, and to a close friend, he was also showing signs of dementia [35].

[1] Oberholzer op cit

[2] Weston M J L. Undated but circa 1938. Preliminary Information regarding a business undertaking…, Estate of M J L Weston, papers in the State Archives, Pietermaritzburg, South Africa

[3] Ibid

[4] Weston M J L. Undated. Notepaper for Admiralty Estates, Estate of M J L Weston, papers in the State Archives, Pietermaritzburg, South Africa

[5] Ibid

[6] Jager F A de. 26 June 1951. Affidavit, Estate of M J L Weston, papers in the State Archives, Pietermaritzburg, South Africa

[7] Jackson C. 8 May 1951. Affidavit, Estate of M J L Weston, papers in the State Archives, Pietermaritzburg, South Africa

[8] Rencken Trau. 4 May 1951, Affidavit, Estate of M J L Weston, papers in the State Archives, Pietermaritzburg, South Africa

[9] Jackson C. 8 May 1951. Affidavit, Estate of M J L Weston, papers in the State Archives, Pietermaritzburg, South Africa

[10] Weston M J L. 21 November 1941. Letter to K Weston, Estate of M J L Weston, papers in the State Archives, Pietermaritzburg, South Africa

[11] Ibid

[12] Weston Notepaper op cit

[13] Rein-Weston Kathleen. 29 June 1951. Statement of claim, Estate of M J L Weston,

papers in the State Archives, Pietermaritzburg, South Africa

[14] Weston 1941 Letter op cit

[15] Ibid

[16] Weston MJL. 26 February 1944, Letter to Carl Rein, Estate of M J L Weston,

papers in the State Archives, Pietermaritzburg, South Africa

[17] Rein-Weston Kathleen op cit

[18] Weston M J L Preliminary Information op cit

[19] Rein-Weston Kathleen op cit

[20] Weston M J L. Undated but circa 1950, Letter to Arthur Meikle and Co Ltd, Estate of M J L Weston,

papers in the State Archives, Pietermaritzburg, South Africa

[21] Rein-Weston Kathleen op cit

[22] Weston M J L 1944 Letter op cit

[23] Ibid

[24] Weston M J L. 4 June 1945. Future of “A.E.”, Estate of M J L Weston, papers in the State Archives, Pietermaritzburg,

South Africa, and Weston M J L 1944 Letter op cit

[25] Estate of M J L Weston, papers in the State Archives, Pietermaritzburg, South Africa, South Africa

[26] Rein-Weston Kathleen op cit

[27] Estate papers op cit, and Weston 1944 Letter op cit

[28] Jackson C op cit. This is supported by evidence from passenger lists: Incoming Passenger Lists op cit

[29] Jackson C op cit

[30] Fourie P J. 22 June 1951. Affidavit, Estate of M J L Weston, papers in the State Archives, Pietermaritzburg, South Africa

[31] Weston M J L. 21 May 1946. Letter to F J de Jager. Estate of M J L Weston, papers in the State Archives,

Pietermaritzburg, South Africa

[32] Weston 1944 Letter op cit

[33] McLeod Violet E. 5 May 1951. Affidavit, Estate of M J L Weston, papers in the State Archives, Pietermaritzburg, South Africa

[34] Weston M J L. Circa 1948. Letter to Kathleen Rein-Weston, Estate of M J L Weston, papers in the State Archives, Pietermaritzburg, South Africa

[35] Rein-Weston Kathleen op cit, and Jackson C op cit